Policy & Complex Adaptive Systems

Our goal is no less than the systemic transformation of simple social and environmental policy approaches into ones that are designed to function in complex adaptive systems. These approaches need to be not only highly functional and effective, but also adaptable, efficient under uncertainty, capable of evolving with new inputs, and persuasive in the face of entrenched path dependency. They need to be approaches that function more successfully and sustainably than traditional approaches, delivering more efficient and effective solutions to address urban and rural social and environmental complex adaptive systems challenges.

Russian River Sunset, CA ©Darien Simon

Russian River Sunset, CA ©Darien Simon

Cities face wide-ranging challenges including: inequality, crime, housing shortages, infrastructure congestion, carbon dependency, environmental degradation, and low skills. Local governments are working to address these against a background of prolonged financial austerity, electoral disengagement, misalignments in priorities between central and other tiers of government, rigid funding cycles, organisational silos, and low levels of information, all of which contribute to suboptimal decisions that can intensify persistent problems and degrade public confidence.

Project Proposal, Transformational Routemapping for Urban Environments, an EPSRC (UK) funded Urban Living Partnership Pilot Project; this project was the inspiration for CA:TMaPS.

Some complex things “are not complex adaptive systems. Take the local weather. If the Doppler 3000 forecast on the local news predicts rain on Thursday, is the rain any less likely to occur? No. The act of predicting has not influenced the outcome. Although near-term weather is extremely complex, with many interacting parts leading to higher-order outcomes, it does have an element of predictability.

“On the other hand, we might call the Earth’s climate partially adaptive, due to the influence of human beings. (Have the cries of global warming and predictions of it worsening not begun affecting the very behavior causing the warming?)

“Thus, behavioral dynamics indicate a key difference between weather and climate, and between systems that are simply complex and those that are also adaptive. Failure to use higher-order thinking when considering outcomes in complex adaptive systems is a common cause of overconfidence in prediction making.” https://fs.blog/2014/04/mental-model-complex-adaptive-systems/

Cities, counties, industries, businesses, and community organizations have historically faced social and environmental policy challenges within complex adaptive systems. One significant confounder is the tendency of organizations of all types to view challenges somewhat simplistically by necessity. The filters applied are usually departmental or agency boundaries (silos) defining a narrow view that obstructs grasping the inter- or transdisciplinarity – the complexity – of the challenge. Often, this is a consequence of funding and budget decisions as well as official delineations of responsibility. For instance, departments of transportation are responsible for road maintenance. Planning departments review plans. Sewerage is the province of waste management. Each one may have responsibilities for development and maintenance of particular geographic areas, but they may work entirely independently of each other. A road could be built out to a prospective development area by transport, then have parts dug up to install sewerage and other infrastructure by waste management once plans are approved. Or, construction could have exacerbated difficulties in new construction or repair by driving development in one direction (where roads already exist) when another might have been preferable (to avoid additional sprawl or building on greenspace). This latter is an example of path dependence, a characteristic not entirely unique to complex systems.

Traditionally, efforts to intervene or resolve policy challenges within complex adaptive systems have focused on a silo – one aspect of the challenge (getting the homeless off the streets) – rather than the interlinked system of issues from which the challenges emerge (medical bills, lack of education, mental health or addiction issues, etc.). Now, with covid-19, those challenges are even more complex than they were before.

Policy challenges within complex adaptive systems have often defeated efforts to address them, sometimes with some improvement until circumstances negated progress, occasionally with unanticipated consequences, and in rare situations the solutions have been catastrophic failures with unexpected negative impacts:

-

- mid-20th Century low income housing projects, some of which were being demolished long before their expected lifespan due to the unanticipated negative impacts of concentrated poverty;

- racial and gender inequalities, often addressed through simplistic approaches to only one aspect (e.g. workplace discrimination) instead of examining their systemic roots and interactions; and

- climate change, one of the most systemic and complex issues humans have ever faced, and one that is dramatically impacting society in 2021, and beyond.

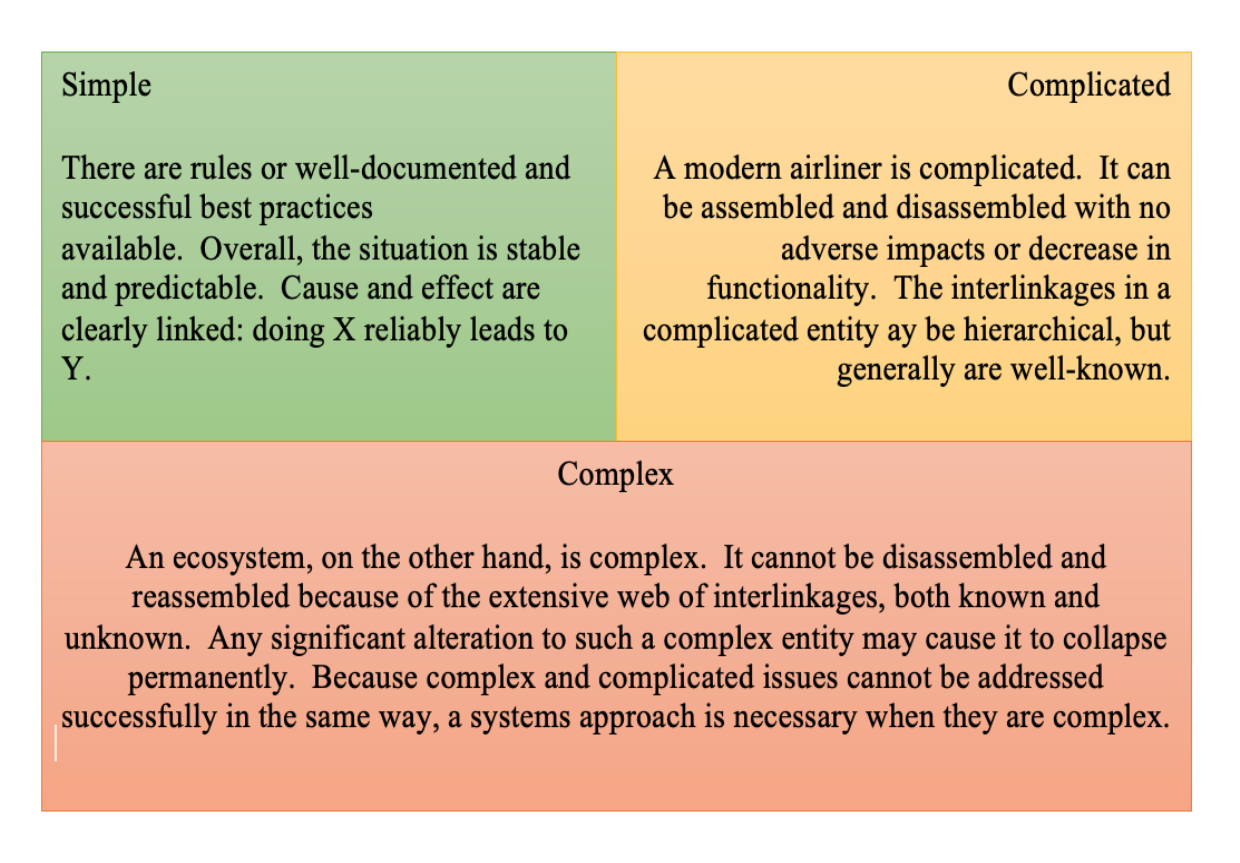

These failures, or less-than-optimal, unsustainable results, can be attributed, in part, to characterisation of the challenge as either simple or complicated, and not a policy challenge within a complex adaptive system. Assuming that these challenges are simple enough to be deconstructed into manageable component parts, respond proportionately to solutions applied, and are consistent over time, amongst other things, prolongs their intractability.

Complex adaptive systems do not respond predictably to simple, targeted policy solutions.

Simple solutions are out of their league in addressing policy challenges within complex adaptive systems, which is why they so often fail.

A More Functional Conceptualization

A complex adaptive system is one in which policy choices made can feed back into the system, changing the fundamental system parameters and dynamics unpredictably. Climate change is one example, however, many other intractable problems can be characterised as policy challenges within complex adaptive systems:

- income inequality,

- poverty,

- homelessness,

- racism,

- sexism,

- declining neighborhoods,

- increasing disease risk, and

- other public health issues, etc.

These challenges cannot be deconstructed into elements that are then successfully resolved independently of each other, and X does not necessarily lead to Y.

Policy challenges within complex adaptive systems require an entirely different approach, one that is adaptable to uncertain and changing conditions, inclusive and collaborative, and nimble enough to adjust to disproportional or inconsistent responses with minimal loss in efficiency and effectiveness.

To develop the necessary new policy approaches, several questions require consideration:

-

- What new ways of working are needed by policy delivery teams to learn to apply a complex adaptive systems approach to solutions?

- How many different perspectives are needed to optimise the set from which proposed solutions are drawn?

- How can teams effectively build networks to collaborate across disciplinary boundaries?

- What systemic changes are required in organisations, agencies, and teams to facilitate adoption of the new ways of working?

- How can teams design policy delivery to improve efficiency and satisfaction with sustainable project outcomes?

CA:TMaPS Elucidates

The CA:TMaPS innovation is to apply a complexity-based systems approach to social and environmental policy issues. We incorporate the latest science to improve success, facilitate development of organisational resilience in the face of uncertainty through participatory processes, and offer teams and organisations the opportunity to learn how to transform how they work into more effective, efficient, successful, and sustainable forms.

CA:TMaPS can assist governments, community groups, businesses and industries, or any other team, interested in developing sustainable solutions to social and environmental policy challenges. We bring complexity into explicit consideration for policy design and delivery through our CA:TNP© process that trains teams to identify complexities in their delivery environment and incorporate that knowledge into action planning for policy design and delivery.

CA:TNP© trains teams to rethink how they understand and address complex challenges by:

-

- Learning new ways of thinking about challenges by making the complexities explicit through structured questions. The more thoroughly they are explored, the more accurate and targeted the input into planning and delivery of solutions.

- Finding common ground with people from different backgrounds, disciplines, industries, and communities. Broader collaborations have increased satisfaction with solutions and their implementation by improving the range of inputs and options available for consideration.

- Thinking creatively and adaptably, improving team understanding of the complexities and the skills required to address them. This creates an environment of exploration beyond the traditionally applied solutions, which often are limited to one aspect of a complex challenge (“remove the homeless from neighborhood X”), and so, doomed to fail.